Crashing The Party (Hungary's Road to Freedom)

If you ask me how it all started, I'd have to tell you that I don't know. If you ask me how it will end, I'd say, who knows?

In fact, I've never raised these questions with myself. Asking and answering needs stopping and thinking, and during these years I have not had time to meditate on them. Now, being away for three months from Hungary as a visiting fellow to the United States, I have been asked the ominous question many times:

How did I get involved in the political transformation of Hungary?

My father, the son of a country teacher, was in World War II. He was captured by Soviet troops at the end of the war in Hungary while on his way home and sent to Armenia as a prisoner of war. By the time he escaped in 1948, the communists had taken over Hungary.

My father joined the Communist Party to protect his dad, who was not in favor of communism. They both were teachers in the same small village and my father soon became the school's director.

Paszab - a small village in East-Hungary, 1960s

But I never joined the Communist Party.

My mother, the daughter of a Calvinist minister, used to read the bible in English in the mornings and evenings behind dark windows. I also was baptized in our home, not in the church, for the same reason.

Yet, under the influence of communist ideology, I did not become a religious person.

I left home at 14 to attend a well-known boarding school owned by the Protestant church before the communists took over. This was in the mid '60s, when communist ideology was at its peak. That school, nationalized by the state, still preserved a lot of its cultural traditions, yet l remember having mandatory lessons reading the party newspaper every Sunday morning. And it was natural for everyone to belong to the Communist Youth Organization.

But I could never stand rigid rules and regulations so common in high schools in those years. I much preferred the music of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, a music expressing our feelings of rebellion, wearing shocking clothes, having long hair, smoking, drinking alcohol and breaking rules. No wonder I was kicked out of the student hostel where I lived.

The graduate class of 1969

After a ’memorable’ year in the Army, I attended the university studying English and history in Debrecen, a cultural center in Eastern Hungary. I listened to and played rock music, worked for the college radio programs and contributed to the university newspaper. That was the first half of the '70s, the years that pushed back Hungarian economic reforms. Yet, finishing the university, we believed that Marxism was an advanced social theory, albeit badly executed. We even thought it would be our task to demonstrate how it could be directed on the right course. We hated corruption and the rule of the privileged bureaucracy.

A group of like-minded, professionally devoted beginners, we started our job at the local daily paper trying to figure out how to accomplish that. But we began to find ourselves and the country more and more in a jungle of tragically false ideas and misbeliefs. I realized I could become one of the evil spiders weaving the net of these lies.

Thank God, my instincts to all forms of injustice and oppression helped me avoid falling into the dangerous trap. I was quite insistent on not using the term "socialism" in my stories. In a country where the primary role of the press was the interpretation and transmission of state ideology, it wasn't an easy task. The argument sounded always the same: anyone working for the party paper should accept these rules of the "game." And I always had the same answer: "Well, show me another paper in town I could work for as a journalist".

This was, of course, a theoretical debate. Our paper was the only one in the county, and the Communist Party owned all the local papers.

'Delete it yourself’

For 10 years I worked in the newspaper's cultural (features) department mostly as a theater and music critic, away from politics. However, my conflicts at the paper increased as the years passed. Un-like other "socialist" countries, we didn't have institutionalized censorship. As a means of control, the managing editors were members of the Communist Party. In addition, we were expected to act as our own censors. My editor used to say, "Whoa, pal, why do you wanna do me harm with these sentences of criticism in your story? Isn't it better for both of us to delete them yourselves?"

There was just one answer for these kind proposals.

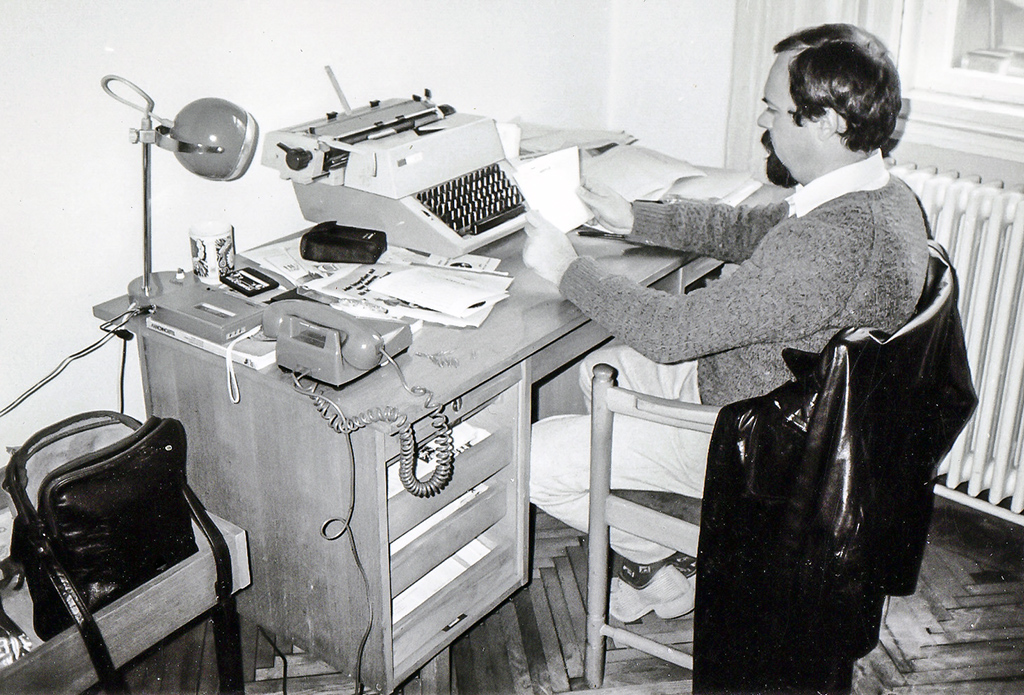

In the editorial offiice of the daily Hajdú-bihari Napló, late 1970s

I was invited to join the party a couple of times. I resisted, because I preferred my independence and moral integrity. There was no question I had hardly any prospects for a career at the paper. I didn't care too much. I was young and still believed I could have my own thoughts and ideas and express them.

But as my consciousness grew, more and more of my stories of criticism were refused. In the middle of the '80s, I began to think about leaving the paper though I had nowhere to go. Conflicts reached a peak in 1985 when we discussed the draft of the new ethical code of the Association of Hungarian Journalists. We had high-ranking representatives of the association and the secretary of the county committee of the Communist Party to attend the session.

The first sentence of the draft started as follows: "It is the duty of Hungarian journalists to collect, interpret and publish their pieces of information with loyalty to Socialist Hungary."

At the beginning of the meeting, I raised my hands and suggested the following amendment: "It is the duty of Hungarian journalists to collect, interpret and publish their pieces of information with loyalty to facts and the truth."

As we say, the knife seemed to stop while cutting the air. The managing editor, white-faced, shouted at me, "The word 'socialism' cannot be deleted from the ethical code of Hungarian journalists!" He put my proposal up for vote. Not surprisingly, no one voted for it although most of them agreed with me.

Among students again

But this was not the end of the story. The party secretary decided to set an example by punishing "that dangerous representative of the local opposition." He insisted I be fired. However, not even the managing editor wanted to get rid of me, though I unquestionably caused him the most conflicts. Instead, he soon proposed me as editor-in-chief of the university paper, published by the same company.

Debrecen's six-page college paper was published every third week, so I couldn't have found a more comfortable job. This was in 1986, and as an intellectual, I made plans to improve my education and read dozens of books.

This was not the way it happened.

It is part of Hungary's national consciousness that from the freedom fight against the Austrian emperor in 1848 to the revolution in 1956 against the Soviet occupation, Hungarian youth and university students have always been the generating force of change. At the university paper, I met open-minded students who radically opposed the system. It soon developed to a mutual voice of protest and criticism.

Some of the outspoken editions were sold-out and circulated in Xeroxed copies. The editorial work was controlled by the chief of the Communist Party of the university. There were times when stories almost were rejected, but the socialist system was going through so much trauma that the committee just didn't have any more power.

It was a situation partially caused and used by us.

The tent for democracy

In September 1987, as a sign of the agony of the system, the cream of Hungarian intelligentsia met in Lakitelek, a village in the countryside, to discuss the direction to be taken by the opposition. The meeting marked the birth of the Hungarian Democratic Forum (HDF), a group of intellectuals representing national values and democratic ideas.

HDF soon set out to organize panel discussions in Budapest, covering such themes as democratic constitution, the role of the media and the problems of Hungarian minorities living abroad. I attended some of them, and asked the organizers to provide my paper with a survey about their projects. They sent a letter with an invitation for the next meeting in Lakitelek on Sept. 3, 1988, a date that started a new era in Hungarian history.

I felt I had to be there.

The meeting, again, was hosted by one of the founders of HDF, a teacher and writer living in Lakitelek. There were still some fears of police intervention among the 3oo participants arriving from all parts of the country, but nothing happened On the contrary, delicious Hungarian stewed meat and fine local wines were served, while the leaders of the forthcoming silent revolution delivered speeches in a huge tent on the future directions of Hungary should take. The outcome was the declaration of the Hungarian Democratic Forum as a national intellectual-political movement aimed at fighting for human rights and democracy.

It was a delightful and unforgettable day. Hundreds of committed and socially conscious people were looking for the same direction. I decided to join the party the same evening. I received a card with the number 145.

Ears on the phone

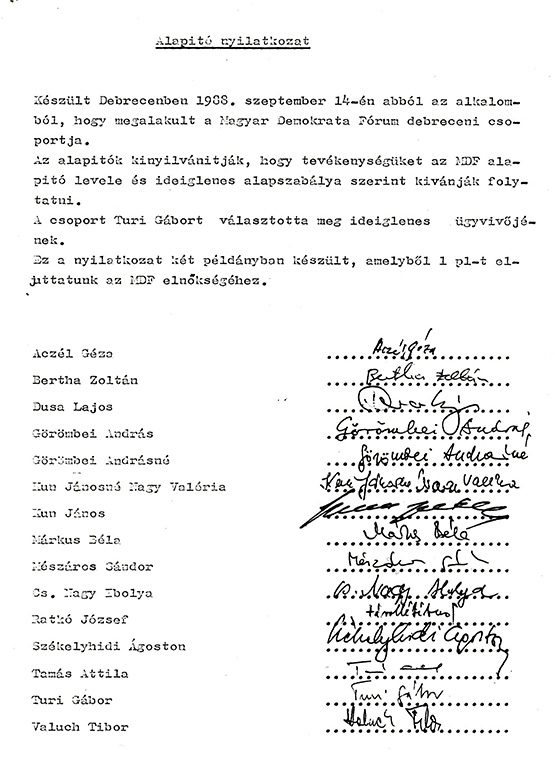

About a dozen people from Debrecen attended the meeting. When we returned home, we decided to form a local group. On Sept. 14, 1988, we met in the editorial office of Alföld (The Great Plain), a literary monthly. We knew it would be the first organized group to oppose the communist regime after 44 years, so there was excitement during the meeting.

The declaration was signed by 16 writers, university professors and intellectuals, including myself. To my surprise, I was elected acting secretary.

It was an honor to enjoy the trust of those venerable people and understood something new would begin, but I didn't have any idea of the scope of responsibility.

Founders of the Debrecen branch of

Hungarian Democratic Forum, 1988

The next day, the local paper published a short news item on the event. I received many phone calls and visitors who wanted to join the movement. (HDF declared itself a political party some months later, in the summer of 1989.)

In the evening, after the last visitor left my home, my wife desperately expressed her concerns that our lives would be disrupted and that the secret police would tap our phone. I tried to quiet her, telling her the group didn't have any secrets, that this was an open organization, and that the system was changing.

But my wife proved to be right. Our life completely changed from that day. Up to then, I had been a journalist earning a reputation for open-minded commentaries. From then on, I was treated as the leader of the first movement opposing the system. I no longer was a private person.

The following weeks found me and my friends feverishly setting up the organization. We met once a week. A month after forming our group, we announced an open meeting for the public. The university was progressive enough to provide venue for the event, which attracted some 400 people, including some curious ones from the Intelligence Service.

We discussed the country's situation and defined goals for the local division of the party. Greeting us were two of the party's founding members from Budapest (one is Hungary's secretary of defense now).

Oct. 14, 1988 was a historic event in Debrecen. Not a small group of intellectuals anymore, the local branch of the Hungarian Democratic Forum was born and began openly fighting communism, working to introduce a parliamentary system and a free market economy.

Fears and hopes

In the autumn of 1988 and the winter of 1989 I was completely involved in setting up the party organization, including various committees covering economy, education, health care, environmental protection and law. I emceed meetings and delivered speeches, working hard on making our ideas widely known. For a long time, we met fear and mistrust. We were still, after all, the opposition.

For months I was away from my wife and two daughters five or six evenings a week. In March 1989, at the party's first general assembly in Budapest, I was elected to the national board.

Meanwhile, my professional life had changed radically. Three friends from the local newspaper and I started the first independent weekly in the provinces. Forming a limited company of banks, co-operatives, retailers and private entrepreneurs, we set up an economic base for the paper, which first was published March 15, 1989.

There were four of us on the staff, so we had to work extremely hard. I loved this job, but after a long, hot summer I realized that working as editor and being involved in politics didn't fit well. So I accepted an invitation by the editor-in-chief of the national weekly newspaper Hungarian Forum to join them as a correspondent from Debrecen.

I started working there on Jan. 1, 1990, but progress in politics soon made it clear I wouldn't be able to focus on writing. The date of the first free elections after four decades was fixed for March 24 and, as a member of the HDF national board, I was assigned to head the campaign in my county.

Run for victory

Oh, that stormy spring of 1990! My wife, who had had enough of my political activities by then, talked about divorce. But could I have any other option than to proceed on what would crown our 18 months' efforts in fighting for democracy in my country? Fighting for peace with my family seemed easier so I asked for more patience and jumped into the water again.

We had just begun studying and practicing democracy, so we had to find out everything about political campaigns by ourselves. I travelled around the county, delivering speeches and putting up posters. Every Friday, I drove to the capital for meetings and transported posters, flags, and badges back to Debrecen. Sometimes my small East-German Trabant car seemed like it would fall apart. There were nights when I was so tired on the way back home that I had to sing and shout to stay awake during the 150 mile drive.

The most difficult job was to select the right people for each constituency. I was supposed to head the local party list and could have become a member of parliament in Budapest, but I decided not to be away from my family.

The elections brought a bright victory for my party, winning six of the nine constituencies in the county. The Hungarian Democratic Forum became the strongest party in the land and formed a 57 percent coalition with its partners, the Christian Democratic Party and the Smallholders' Party. What a joyous celebration did the walls of the party headquarter see that night in Debrecen!

The night of victory, general elections, April 8, 1990

We were extremely happy to have defeated communism, to set the way for democracy, to be free again, and to possess the right for our party to lead the country. We felt like heroes fighting the seven-headed dragon with a single sword.

We didn't realize, however, that the hardest times were yet to come.

The newspaper where I worked folded in the summer because of financial losses, so I found myself on the road in June. Had I become a politician, I wouldn't have faced such problems. I saw no other choice but to join the daily paper in Debrecen, a job I had rejected four years before. I began work as a writer and editor for political affairs.

End of the road

Since then Hungary has been exposed to all the problems of a country being transformed. The liberal opposition – backed by the previously mostly communist, now mostly liberal press – didn't even wait 50 days to start attacking the conservative government.

The parliament became a place for hot debates, frightening people not used to such fierce political fights. A strike by cab drivers, who blocked the streets because of increased gas prices, terrorized the country for a couple of days in October. The economic situation has been worsening, unemployment rising, inflation peaked at 35 percent, and people are likely to recall the good old days when sausage cost almost nothing.

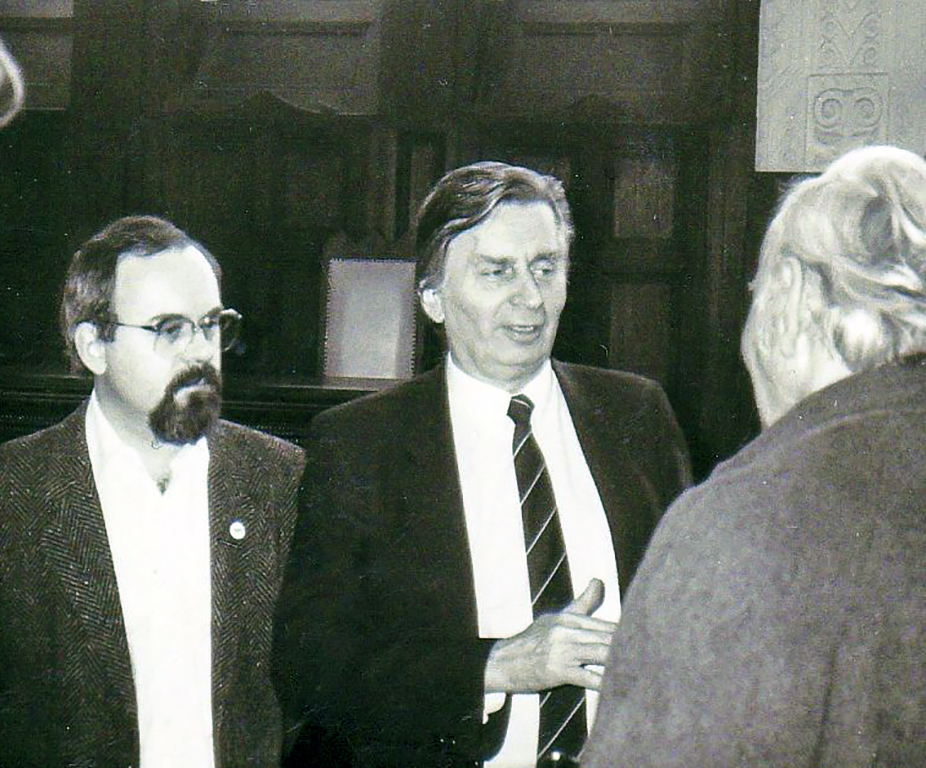

With József Antall, designated Prime MInister of Hungary, 1990

Local elections, held in October 1990, were victorious to the liberal opposition in most of the cities, and the former bureaucracy won in most of the villages. In Debrecen, HDF got only 11 of the 61 city council seats, including mine. If not the national parliament, at least I decided to join the governing council in town.

At the paper, now owned by an Austrian company, I found myself in the same situation I had been in five years earlier. Then, I had to defend myself in a minority position because I didn't belong to the Communist Party. Now, all the ex-communists were becoming independents at the paper and blamed me for being a partisan, democratic though I may be. Fights prolonged. It was the kind of tension that can lead to a heart attack.

The beat goes on

In March, three and a half years after I first became involved in politics, I decided to quit the city council and the Hungarian Democratic Forum as well. I had been attacked by my colleagues and members of other parties for having a conflict of interest. I chose to again become a political independent, at least formally.

My family might have been a bit happier to greet this decision than my enemies.

Now, you may find this story strange indeed, since the beginning is more exciting and colorful than the end. You may also have looked for more personal comments on what happened to me. But don't forget, I am still in the story.

All Hungarians and all Eastern Europeans are in that same news story called the saga of democracy.

We had a couple of heroic months of changing a system, and now we have the painful period of establishing another one. Hopes and fears, expectations and disappointments, joys and sufferings, are just becoming parts of everyday life.

What really counts now is that the last Soviet troops left my country on June 30. We are truly independent and free again – free to succeed and free to fail.

But don't worry about me; I have gained a lot of experience during these years as well as a lot of hope and energy for whatever comes next. For long decades our country was under communism's thumb. Now, I'm looking forward to independent thought and creativity for me, my family and my country.

Would you say this is the place for a "Happy Ending"?

(Gabor Turi was a visiting journalist this summer at The Virginian-Pilot and The Ledger Star)

(The Virginian-Pilot/The Ledger Star, September 8, 1991. Norfolk, Virginia, USA)

The first visit to the US on a grant by the National Forum Foundation, 1991