A day that changed the course of history – the Pan-European Picnic and its perception today

The events of history may be preserved by factual information, the interpretations of scholars and the memories of participants, extending the scope of presentations from accurate statements to personal reminiscences.

On the 30th anniversary of a remarkable day which is now seen as the first in the series of steps in 1989 that led to the collapse of Communism, this is a grass roots account, a personal recollection of the Pan-European Picnic as well as an assessment of its position in the annals of history and collective consciousness.

For me, it all started in September 1988 when the first Hungarian opposition movement, the Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF), had its second historic meeting in the village of Lakitelek in the Great Hungarian Plain. As editor-in-chief of the university paper in the city of Debrecen, I was invited to a session of intellectuals discussing the prospects and the future of the country. Inspired by the spirit of the meeting, I decided there and then to join the MDF, which voted to introduce formal membership. A couple of days later sixteen of us, mostly academics, founded the Debrecen branch of MDF and I was elected its first leader. Those restless months that followed triggered a boom in political activities in Hungary: demonstrations against the planned Danube barrage system, and the systematic demolition of Hungarian villages in Romania were attended by tens of thousands of protesters. At the same time, a series of political movements and parties were born or revitalised. Inexperienced in public affairs, I found myself totally immersed in advertising and organising our party in Debrecen and the region. We soon became the largest independent group in the city, numbering more than 400 people from all walks of life.

Marxist historians generally tend to neglect or deny the role of the individual in making history. One of our members, Lukács Szabó, an economist by education and a farmer by profession, was an ardent adversary of Communism, laying claim to expelling later the occupying Soviet air force from Debrecen and to removing the statues symbolising the regime, including that of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. A radical in his mind, he initiated the invitation of Otto von Habsburg, member of the European Parliament and President of the Pan-European Union, to address an audience in Debrecen about Europe without borders. It was a bizarre idea as the Habsburg Emperor was dethroned at the Great Church of Debrecen on 14 April 1849. Times had changed, however, and Otto von Habsburg was pleased to accept our invitation. His speech, attended by some 2,000 enthusiastic citizens at the great hall of Kossuth Lajos University on 20 June 1989 became a major event.

It was followed by a dinner in the evening, hosted by the local board of MDF in honour of Otto von Habsburg, assisted by his wife and eldest son, the young George, in a parlour of the famous Golden Bull Hotel. It was there, during a friendly conversation that Ferenc Mészáros, a board member, raised the idea of a future meeting with the Habsburg family, a so-called open-air bacon roasting party at the Austro-Hungarian border to celebrate the bonds between Austrians and Hungarians. I was sitting close to them and later that evening conducted an interview with Uncle Otto, as we would call him, to be published by a newly formed independent weekly paper that I worked for as editor, ÚTON [On the Road]. He was a very outgoing person with an excellent command of Hungarian, often using the term “we, Hungarians”.

One may speculate: if it had not been for Lukács Szabó, the idea of a Habsburg visit to Debrecen, the dinner at the Golden Bull Hotel, or the plan of a picnic at the borders would not have happened – and, most likely, the process leading to the fall of the Berlin Wall would have been delayed as well. Of course, for the success of the event the cooperation of some MDF leaders, and the complicity and background support of the reform Communist leadership, Miklós Németh and Imre Pozsgay in particular, was also indispensable.

A couple of days later Mészáros submitted the proposal to the local MDF board whose members, because of the distance and the shortage of time (the picnic would be scheduled for 20 August), abstained from expressing their full support. I was also cautious as the idea seemed to evoke the notion of the so-called World Youth Meetings, an international campaign pioneered by the Communist countries. However, there was one person, Mária Filep, who found the idea a challenge to rise to. She was disturbed by the recently erected barbed wire by the Romanian authorities on the eastern border of Hungary to stop refugees, mostly ethnic Hungarians, escaping from the country. She began working on the project and soon put forward an extended version of a mass gathering, including a symbolic dismantling of the Western border. Her idea was to connect the picnic with a meeting of intellectuals and opposition activists from Central and Eastern European countries, under the name Common Destiny Camp, to be held in Martonvásár, at the one-time Brunswick Mansion south of Budapest, around the same time.

Despite having no internet, no mobile phones, no telephone at home, not even a long distance line in her office at hand, Ms Filep set out to organise the meeting risking her job. She worked as an engineer at a state-owned construction company of 3,000 employees. She was Lady Willpower, with a stamina and a vision that was destined to overcome any obstacles. She recruited volunteers and soon made contacts with top officials in ministries and the headquarters of the border guards to secure official permission for the event. She invited the reformist politician Minister of State Imre Pozsgay as well as Otto von Habsburg to act as patrons of the meeting, a gesture that was welcomed by both of them. Eventually, the name Pan-European Picnic was coined.

A piece of the Berlin Wall in the Memorial Park

The event was intended as an informal meeting of Austrians, Hungarians and people from European countries at a border meadow. Debrecen is located about 470 kilometres from the Austrian border. We had no on-the-ground knowledge of the area, long closed to visitors due to the Iron Curtain, and received little information about the dismantling of the barbed wire that had been started by the Hungarian authorities on 2 May. As it turned out, there was nothing left of the formidable technological barrier zone called the Iron Curtain by 19 August, except for a short section aimed at holding up stray animals. That was the site chosen for the picnic in Sopronpuszta, an old border crossing point out of use since 1948.

We knew that without the assistance of partners in western Hungary the whole project would have been jeopardised. Filep began to make contacts with opposition parties in the region and finally received a positive reply from activists of the Hungarian Democratic Forum, the Alliance of Free Democrats, the Smallholders’ Party and the Alliance of Young Democrats in Sopron. László Magas, Zsolt Szentkirályi and others offered full support and became key figures in the fieldwork. Based on their local knowledge, they took care of logistics and, what is more, extended the scope of the event by suggesting to the authorities and arranging a temporary opening of the border from 3 p.m. to 6 p.m. on 19 August, including mutual visits by delegations from both the Austrian and Hungarian sides, as well as printing flyers in Hungarian and German and coining the slogan of the picnic, i.e. “Cut and Take” (pieces of the wire).

We were all motivated by the yearning for freedom, a desire for the transparency of the borders, the recognition of the common destiny of peoples, and the notion of European unity. My role as a journalist was to inform the media about the gathering. It was my initiative to send letters of invitation to about 30 Embassies based in Budapest with the aim of generating international exposure.

* * *

The volunteers in Debrecen left for Sopron at dawn on 19 August by car, two buses and a truck, carrying all the necessary materials with them for the picnic, such as logs, bread, bacon and onions provided by local entrepreneurs. I may have been one of the few Hungarians who approached the site from the other side of the border, that is Deutschkreutz, an Austrian village across the Kópháza border crossing, a couple of miles south of Sopron, where I stayed with my wife and two daughters at the house of our Austrian friends. Driving my light blue Trabant, the proverbial East German two-stroke engine car with a plastic body, which I owned for reasons other than my affection towards the country it was imported from, I saw a good number of similar vehicles abandoned on the road, equipped with East German licence plates. A strange sight but, with no GPS at hand, I had to focus on finding my way to the spot where I joined my fellows from Debrecen. We started to make preparations for the picnic, about a mile from the border, without any notion of what would happen in the afternoon.

By noon, about 8,000–10,000 thousand people had gathered in Sopronpuszta. A joyous, friendly and slightly chaotic atmosphere prevailed, hardly hindered by a heavy rainfall which cut the campfires short. The official programme of the picnic started late afternoon on a stage that was set up for the speakers, including László Vass representing Imre Pozsgay, Walburga Habsburg in the name of her father, as well as Hungarian writer György Konrád, and Klaus Lange, President of the Austrian Branch of the Pan-European Union. The message by Bishop László Tőkés, who would later become the initiator in Timişoara of the so-called Romanian Revolution and who was under house arrest at the time, was read out, again, by Lukács Szabó who had managed to smuggle the text to Hungary a couple of days prior to the event. The manifesto of the picnic, symbolised by a white dove, designed by Ákos Varga and printed in eight languages in Debrecen, was distributed among the audience.

The Visitors’ Centre, unveiled on the 30th anniversary

Early afternoon, under the pressure of the international media, the key organisers decided to arrange a press conference in Sopron. The opening of the border crossing was scheduled for 3 p.m. for people with a valid passport, but five minutes before that time some 40–50 East Germans, who had been hiding in the forest, rushed to the scene and broke through the dilapidated wooden gate. The armed Hungarian border guards had no clue what to do. Fortunately they did what the situation suggested, i.e. took no action to prevent the East Germans from illegally crossing the border. Ironically, the VIP persons happened to miss the historic moment. It was half an hour later that some of them arrived on Bratislava Road, full of excited people on both sides. For a photo op, the gate was closed and reopened by Mária Filep and László Magas, representing Debrecen and Sopron, an act which made way for a new wave of East Germans, numbering 600–700, to get through. This was the picture that circulated all over the world, similarly to the simulated wire-cutting action at a reinstalled section of the barbed wire for a media presentation by Austrian and Hungarian Foreign Ministers Alois Mock and Gyula Horn, respectively, on 27 June.

In the evening, quite tired, I drove my car back to Deutschkreutz where, watching the news on Austrian TV channels, I finally had an overview of the happenings of the day, including the most significant moments, i.e. the breakthrough of East German refugees to the free world – which I had easy access to by then, using my Hungarian passport. I came to realise that the incidents would overshadow the original vision and meaning of the event. And that is what happened: the day of the Pan-European Picnic became of historic importance, the first step in a series of events leading to the fall of the Berlin Wall, as German Chancellor Helmut Kohl stated in 1991.

* * *

As significant an event as it turned out to be, however, the perception of the picnic has been distorted over the past decades. The first piece of information on the civil organisation of the project was reported by the Hungarian secret police in Debrecen on 10 July, falsely attributing the idea of the picnic to Otto von Habsburg. This fake news has repeatedly been published by the media, never questioned nor denied by the Habsburg family. Rather, they keep on emphasising their role in the Pan-European Union as organisers, a contribution most likely materialised by advertising the picnic and recruiting visitors from Austria.

In his memoir (Koronatanú és tettestárs [Star Witness and Accomplice], 1998), Minister of State Imre Pozsgay recalled his encounter with Otto von Habsburg who identified himself as the originator of the picnic idea; a statement that was published as factual information by the historian Ignácz Romsics in his books on the transformation of the regime (Volt egyszer egy rendszerváltás [Once Upon a Time There was a Regime Change], 2003 and Rendszerváltás Magyarországon [Regime Change in Hungary], 2013). Similarly, in a public speech in September 2019, Miklós Németh, Prime Minister of Hungary in 1989, based on their conversation, named Otto von Habsburg as initiator of the picnic.

In contrast with these statements, Otto von Habsburg, in a letter signed on 22 July 1989, and sent to the organisers in Debrecen, wrote: “As a re-elected member of the European Parliament and President of the Pan-European Union, it is my pleasure to welcome the initiative by my fellow citizens in Debrecen to organise a Pan-European Picnic aimed at finally parting the barbed wire at the Hungarian–Austrian border.”

This was the first sentence of a text read by Walburga Habsburg as her father’s message on stage at the picnic on 19 August 1989.

Changing the angle of view and calling common sense on board, the question whether it was a plausible option for the heir apparent of the House of Habsburg to propose a meeting, an open-air bacon roasting with a bunch of obscure people from Debrecen at the Hungarian–Austrian border, should also be addressed.

The misrepresentation of the events is also shown by the overwhelming presence of the city of Sopron in the subsequent media coverage of the recent 30th anniversary. Both the international and the Hungarian press keep publishing stories on the picnic, mostly based on its interpretation by the organisers in Sopron, and not always from a balanced point of view. In 2017, Hungarian Public TV premiered a documentary focusing on Sopron and its people including Árpád Bella, commander of the border guards with hardly any reference to the organisers in Debrecen.

Admittedly, the site of the picnic is much closer to Sopron than to East Hungary, a fact that makes Sopronpuszta the right place for the memorial park that is constantly evolving. Sopron has promptly recognised the importance of the events and made it a brand of their own, whereas Debrecen, partly due to the distance, has only sporadically promoted the image of its role in the picnic. Yet, it is a fundamental fact that 19 August 1989 was a joint effort by dedicated citizens from both Debrecen and Sopron, a dual enterprise that should earn a place in history accordingly. Debrecen, the city of freedom reached out and shook hands with Sopron, the city of loyalty, as it was famously called after its post-Trianon treaty decision to be part of Hungary rather than Austria. It was a gesture honoured by high decorations by the Hungarian government awarded to the key participants, recognising the merits of both sides at the 15th anniversary.

Naturally, a shift in the public awareness of the picnic from a jovial gathering by origin to the dramatic breakthrough of East German refugees that captured the attention of the world is a legitimate tendency. We were aware of the news in the summer of 1989 about the growing number of East Germans travelling to Hungary in the hope of escaping to the West, yet their exodus took everyone by surprise. They were informed about the date and site of the picnic by thousands of flyers printed in German, reproduced and distributed by hands still unidentified.

* * *

Harking back to the day 30 years later, we have a culmination of unforeseen and unexpected events on our mind that helped accelerate the decision-making process of the Hungarian authorities to solve the refugee problem. The official opening of the border to East Germans on 11 September 1989 was a risky and brave move by PM Németh. We can be pleased to see the basic ideas of the Pan-European Picnic realised by Hungary joining NATO in 1999 and the European Union in 2004.

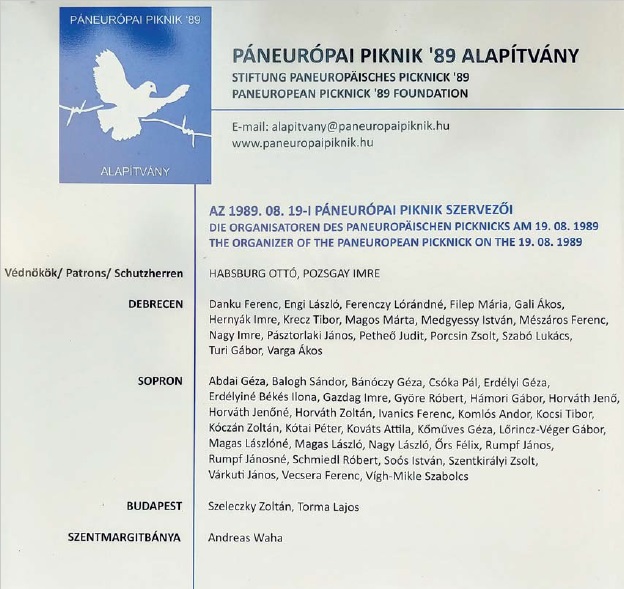

The organizers’ names displayed in the Memorial Park

What started as a private initiative by civilians in June 1989 has, over the decades, become an item on the agenda of international politics. Interestingly enough, it was Germany that started to celebrate 19 August, the day of the picnic, as opposed to 11 September. It was marked by the visits of Chancellor Angela Merkel both at the 20th and at the 30th anniversaries. For the first time in 2019, in addition to the key actors, some of the participants from Debrecen were also invited and hosted by the city of Sopron.

(Hungarian Review, 2019)