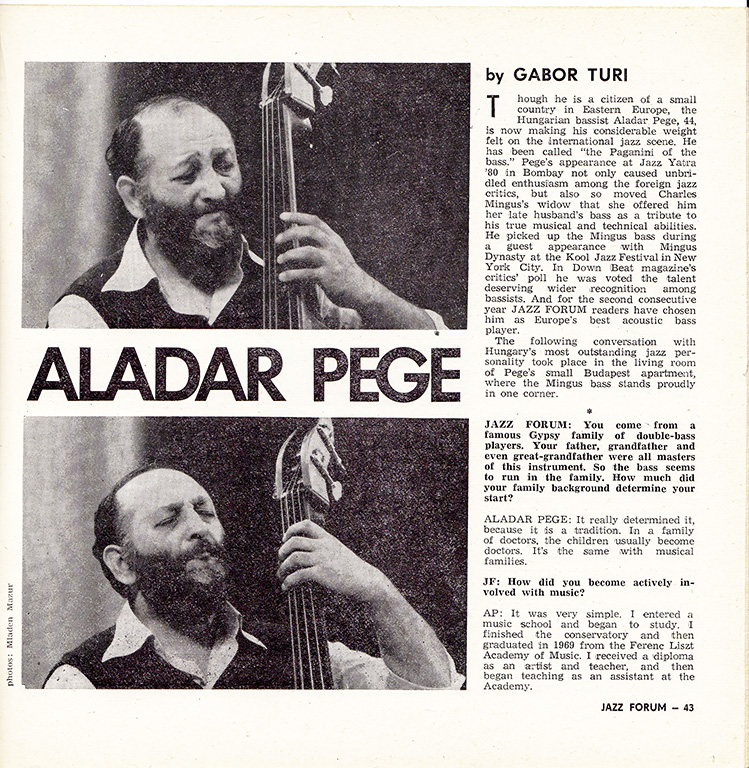

Aladár Pege (The Interview)

Though he is a citizen of a small country in Eastern Europe, the Hungarian bassist Aladár Pege, 44, is now making his considerable weight felt on the international jazz scene.

He has been called “the Paganini of the bass”. Pege’s appearance at Jazz Yatra ‘80 in Bombay not only caused unbridled enthusiasm among the foreign jazz critics, but also so moved Charles Mingus's widow that she offered him her late husband’s bass as a tribute to his true musical and technical abilities. He picked up the Mingus bass during a guest appearance with Mingus Dynasty at the Kool Jazz Festival in New York City. In Down Beat magazine’s critics’ poll he was voted the talent deserving wider recognition among bassists. And, for the second consecutive year, JAZZ FORUM readers have chosen him as Europe’s best acoustic bass player.

The following conversation with Hungary’s most outstanding jazz personality took place in the living room of Pege's small Budapest apartment, where the Mingus bass stands proudly in one corner.

JAZZ FORUM: You come from a famous Gypsy family of double-bass players. Your father, grandfather and even great-grandfather were all masters of this instrument. So the bass seems to run in the family. How much did your family background determine your start?

ALADÁR PEGE: It really determined it, because it is a tradition. In a family of doctors, the chilrdren usually become doctors. It's the same with musical families.

JF: How did you become actively involved with music?

AP: It was very simple. I entered a music school and began to study. I finished the consarvatory and then graduated in 1969 from the Ferenc Liszt Academy of Music. I received a diploma as an artist and teacher, and then began teaching as an assistant at the Academy. I am not a jazz musician, but rather a double-bass artist and teacher who plays jazz as well. I can play every musical style from baroque to free jazz. Since 1963, I have been performing classical music and jazz in concerts. So far it’s happened that the first part of the concert is classical music, the second is jazz.

JF: There are only a few examples of musicians who have their feet in both camps, so to speak.

AP: But I always wanted to be a concert musician playing classical music.

JF: And how was jazz related to this desire?

AP: Well, I had to make my living while studying classical music. At that time, in the ‘50s and ‘60s, there were few possibilities other than playing in restauirants. It payed better than symphony orchestras, even today that’ so. I only stopped doing this in 1970.

JF: So this was a means to have the financial basis to make yourself independent.

AP: Yes. In those days everybody had to play in restaurants, there were hardly any opportunities for playing jazz in concerts. But the musicians, especially the pianists, were highly educated. Almost all of them had graduated from the music academy. It was not without reason that they began enjoying fame and popularity abroad. Of course, their music was not pure jazz because it couldn't have been, but they knew the instrument perfectly. Today only some of the jazz musiciains have an academic diploma.

JF: What kind of music did you prefer at that time?

AP: Whatever we had the opportunity to listen to: West Coast, cool, bebop, swing...

JF: It was hard in the ‘50s when the cultural leaders declared jazz to be a “crisis product of imperialism” and prohibited its performance. About the only outside source of jazz was Willis Conover’s broadcasts. Fortunately, things have changed since then. But I am curious as to which musicians had the strongest influence on your development?

AP: The whole West Coast line: Russ Freeman, Bud Shank, Shorty Rogers and the others. Then Donald Byrd, Lee Morgan, Clifford Brown. Later Charlie Parker. I managed to listen to Chet Baker's recordings even before Charlie Parker's.

JF: And what about the bassists?

AP: Ray Brown, Oscar Pettiford, Charles Mingus, Scott LaFaro.

JF: Whom do you respect the most?

AP: Well, I like many of them. One I like for providing a nice accompaniment, the other for being very musical, the I third for having good ideas, the fourth for possessing a perfect technique. But today I have reached the point where if you put on a record you can identify whether it is Ron Carter or Aladár Pege.

JF: And what do you attribute for your becoming a maestro on the instrument: your talent, good teachers, the circumstances, your persistence or something else?

AP: All of the above. My teachers certainly didn't have bad qualifications. For sure, there was Prof. Rainer Zepperitz, the leading bassist of von Karajan at the Berlin Philharmonic, who had the greatest impact on me when I stayed in West Berlin from 1975-78. I have always been studying and practicing classical music. I have never played jazz exercises, except for pizzicato finger movements. You know, things develop further if someone raises the level and finds himself work that exceeds the abilities of the instrument or differs from the average. But this requires a lot of thinking and practicing. You have to be different from the others. You have to develop a different pizzicato technique – I succeeded. A different fingering pattern, different changes of positions – I did it. But you must have a special gift for it.

JF: What do you mean by this?

AP: The ability to find out non-customary things. For example, you need a special pizzicato technique to carry over to jazz the knowledge gained by practicing classical music. Years ago bassists used to play with one, sometimes with two fingers; today they play with two or even three. But this is not enough, if your right hand doesn’t move together with the left or vice versa. Not to mention other means. But first of all, you must be talented. It is not useless if someone is born to the instrument.

JF: So you would say you were born to it?

AP: Well, it seems so. In contrast to many talented musicians the glory has not confused my mind. I know I have to improve my technique and this gives me inspiration.

JF: How much do your practice regularly?

AP: Nowadays not too much; it depends on my time. I play a lot of concerts abroad, even more in Hungary – classical music, jazz, everything. If I have time, I practice; if not... But there were years when I used to practice six hours every day.

JF: How would you describe the technique you have developed over the years?

AP: I think many musicians have tried to play violin pieces on the double-bass. I play a lot and intend to do so in the future, too. You know, it requires special gifts, because the double-bass is the most difficult of the string instruments.

JF: And in jazz?

AP: It’s an easier situation, because everybody is improvising. If he has the capacity at all, that’s what comes to his mind. You should have the intelligence and musical knowledge to avoid playing things you can’t handle. It’s better to play less but well than a lot but badly.

JF: But you play a lot and well...

AP: No, I don’t always play so much either, but I do it constantly. My solos don’t have much to do with the bass; they rather consist of guitar, saxophone and piano figures. It takes years to introduce these figures into your music. Now I play differently than five or six years ago. But this only holds true for the solos.

JF: In jazz history, parallel with the changes of style, we also notice that the manner of bass playing has also been constantly changing. What kind of role do you see for the bass in jazz today?

AP: Its basic job is providing accompaniment for the soloist in order to inspire him. If he plays with swing, you must aocompany him with swing. When it is your tum, you take a solo – that’s your own business. Of course, a good musician stays within the boundaries of the style, but in case he wants to do something else, he can do it as well. The main point is that the rhythm section must be together. You can have a dialogue with the soloist only in free jazz or pieces like that.

JF: That’s interesting because you are among those bassists who have raised the instrument from its purely accompanying function, placing more emphasis on its solo role.

AP: Yes, when I play solos. But when I provide accompaniment, I never resort to any soloistic solutions.

JF: Anyway, your solos are more emphasized and longer than usual.

AP: No! Only if we decide on it in advance, I never play more than the saxophone or guitar player. But it may happen that they are not such strong individuals or can’t play their instruments attractively enough. Of course, they can be good musicians despite this.

JF: Do your improvisations always depend on the situation or do you occasionally prepare something in advance?

AP: I prepare only for classical concerts. You can’t prepare for improvisations. I’ve got my technique. I can play out what I think. Nobody can make plans for solos. A lot depends on the mood of the moment. Of course, if you want to play good music, you should find a structure. You must have a conception and this holds true for all styles. Arrangement and structure can’t be built on the moment.

JF: You have been Hungary’s top bassist almost from the moment you started playing, but in the last few years you have also gained recognition abroad. You are invited to give concerts, make records and the critics often praise your performances.

AP: Well, it’s the consequence of my classical studies. Jazz bassists are usually not so higly educated as their classical colleagues. For instance, in Hungary it was not important for them to play classical music at the academic level. It used to be enough to attend a primary music school and if he had it in the blood, the talent and the feeling, he somehow began to work. But it is more sensational if someone plays the instrument like a master. At the 1964 Prague festival I received the title of “best virtuoso”, although Miroslav Vitous, George Mraz and Ludek Hulan were also playing there. My technique somehow seemed more interesting because of my classical background. And the “Best European Soloist” title at Montreux wasn’t by chance either.

JF: How important is virtuosity in music?

AP: Virtuosity is a great recognition. It doesn’t exist in and of itself, in great airtists it is always combined with expressiveness and suggestiveness.

JF: Could you perhaps explain what you strive for in your playing?

AP: I would like to have no problem with the instrument as far as expression. But because there are always problems with technique, one is occasionally forced to practice further. True virtuosity means to give so much extra out of yourself that your colleagues also feel that they could play it as well. And when they try, they fail.

JF: Nevertheless, it’s often said that technical virtuosity serves to hide the lack of deeper artistic values, thus becoming merely a form of self-exhibition.

AP: That is usually said by musicians less gifted than average who cannot play eight to the bar. Virtuosity doesn’t mean playing fast. In great artists, as I have noticed, it is always connected with expressiveness.

JF: Do you mind having such labels as “virtuoso” stuck to your name or would you prefer to be known in some other way?

AP: I don’t care and it doesn’t bother me, because I do things my own way. It looks like things are working well.

JF: It’s good if someone appreciates his real merits.

AP: I haven’t had to face serious problems. I did have problems with the instrument, and I am still fighting against it, but that’s my own business. I mean music and technique in general, not jazz especially.

JF: It seems that throughout your career you haven’t tied yourself to any one particular style. At festivals you sometímes perform in three or four groups with quite different styles from swing and bebop to free. Which jazz style is the closest and most authentic to you?

AP: I don't know. All.

JF: How can you play so many different styles at the same time?

AP: It’s not difficult at all. This is also a part of one’s musical abilities. A good musician finds it no problem to play different styles. There are only two kinds of music: good and bad. It’s all the same what style you play. For example, Charles Mingus played everything from bebop to free.

JF: But in his case it was a process of developing parallel to the direction of jazz.

AP: It is a process for everybody. Ron Carter also plays everything from rock to free. It depends on one’s education and musicality.

JF: Yet it requires an ability for adaptation.

AP: Yes, but as I said everything depends on whether or not you are a good musician. Every kind of jazz music has a common feature: the swing. Without swing it is not real good jazz.

JF: Given this diversity, what can be described as Aladár Pege’s music?

AP: I have been playing my own compositions since 1963.

JF: And you play your compositions with various formations. Which of these do you prefer?

AP: I don't like to play in groups smaller than a quartet. It would be nice to have more reedmen. Writing pieces and arrangements for quintets, sextets or even larger ensembles offers wider possibilities for me.

JF: There are hardly any Hungarian jazz musicians except yourself who have gained true international fame. But what about your case? How can a Hungarian make it onto the European jazz circuit?

AP: We have to play better or at least on the same level as the foreign musicians to deserve recognition abroad. We can reach it with what is called technique, personality and musicality. I often receive invitaitions from abroad, and if I have time, I go.

JF: As far as I know, there were times when that was not so easy.

AP: To be honest, at the beginning I happened to lose many chances and that still happens to me. I have had to refuse an invitation from Mingus Dynasty three times because they wanted me at once and I couldn’t arrange it. It doesn’t depend on me or the Hungarian authorities. I could go wherever I want to, but it takes three to eight weeks to be granted a visa. I missed many gigs because of that. And what is a career for an artist? Publicity, concerts, television, recordings.

JF: Yet we find your name at the top of the Down Beat poll.

AP: That can be attributed to my recording with Mingus Dynasty. Articles have been written about me since 1963.

JF: You could have chosen another path that many Hungarian musicians followed...

AP: No, I never wanted to leave the country. I have been offered fantastic engagements and assistance, but somehow I was not interested in it. You know, I’ve always had but one cure: to practice and study as much as possible. I practice if I feel sorrow and practice if I am successful. Only in practice, study and work do you find no disappointment. And if he has health and strength, a talented man will succeed even if he doesn’t get support and has to fight alone for recognition. In 1982, I played at Carnegie Hall with Herbie Hancock, Tony Williams, Jimmy Owens and the Marsalis brothers. I was given Charles Mingus’ instrument. I have been playing with almost all the outstanding musicians living in Europe. I suggest for every talented musician the same prescription: study, practice and work!

(Jazz Forum, 1983/6)